The Secert Life Maharani

One of my favorite parts of a recent India trip was staying at the City Palace in Udaipur. This is the seat of the Mewar kingdom—a dynasty of Rajput kings who were never conquered by the Mughals or British. Mewar later joined other Rajput kingdoms in northern India to become the state of Rajasthan after India’s independence in 1947.

While the Government of India does not provide funds to support the old maharajas’ lifestyles and properties, the nobles at least retained their titles and homes. The Udaipur City Palace still has a maharaja living there with his wife and children in a guarded residence, adding to the palace’s allure.

The Life of a Maharani: A Different Perspective

During my visit to the palace museum, I began rethinking what it meant to be a maharani. The zenana, where royal women were kept away from view, felt hot and shadowy due to the intricately carved jali screens that blocked open windows. I was overwhelmed by a sense of confinement. Even the women’s courtyard seemed small and dull compared to other palace spaces.

After this short tour, the life of an Indian maharani seemed more like imprisonment than luxury.

Discovering Autobiography of an Indian Princess

Recently, at the Ames Library of South Asia in Minneapolis, I came across an old book titled Autobiography of an Indian Princess. I knew I had to read it. Fortunately, I found a reprinted edition online to add to my collection.

Written in 1921 by Sunity Devee, the Dowager Maharani of Cooch Behar, the book provides a fascinating insight into royal life. Although titled Autobiography of an Indian Princess, the title is somewhat misleading—Sunity was a maharani, meaning queen. The British referred to Indian maharajas and maharanis as “princes” and “princesses” to ensure they never outranked the Empress of India, Queen Victoria.

Sunity Devee’s Early Life and Marriage

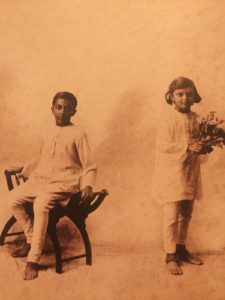

Sunity was born into a respected family in Calcutta. Her father, Keshub Chunder Sen, was a well-known social reformer who converted from Hinduism to the Brahmo Samaj, a faith that promoted monotheism. The British, who admired Sen, persuaded him to arrange a match between his 13-year-old daughter and 16-year-old Nripendra, the Crown Prince of Cooch Behar.

Despite the controversy over Sunity’s young age, the couple’s marriage turned out to be happy. They shared interests in travel, fashion, literature, and high society. Together, they had four sons and three daughters, ensuring the stability of the royal line. Sunity initially spoke only Bengali but later learned multiple Indian languages and English fluently. She frequently traveled to London and became one of the most well-known Indian women in British society.

The Contradictions of Royal Life

Sunity lived a dual existence. In Cooch Behar, purdah and zenana customs restricted her movement. She traveled in a curtained palanquin, cooked, prayed, and focused on childcare within the palace. Her husband forbade her from riding horses or playing tennis. Yet, outside of Cooch Behar, she happily posed for photographs in French couture gowns.

While she adored her British royal friends, she resented how the British treated Indians. In exchange for ruling their lands, maharajas had to pay annual taxes to Britain. These taxes could be increased at the whim of British political agents, who also had the power to audit a kingdom’s finances and even decide a successor if a maharaja had no son.

British Control Over Indian Royalty

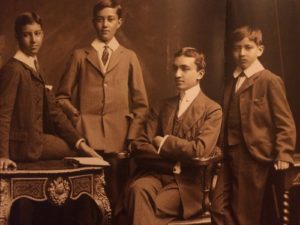

The British tightly controlled Indian royalty, sometimes even more than ordinary citizens. Maharajas couldn’t travel abroad without permission from British agents. These agents dictated where their sons went to school, creating institutions that molded Indian princes into obedient subjects. Nripendra himself attended such a school before completing his education in England.

Sunity wanted her sons to stay home longer, but the British Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal ordered them to be educated abroad. As a result, they returned from Eton fluent in French and Greek but had forgotten their native language.

Cooch Behar’s royal family was considered the most westernized in India. Many envied them, but they lacked real freedom. When Sunity’s eldest son, Rajey, finished his Oxford education and wanted to work with his father’s ministers, the British rejected the plan. Instead, they forced him to join Lord Curzon’s Army Cadet Corps, keeping him from gaining valuable governance experience.

The Fate of Sunity’s Children

Rajey and his younger brother Jit both became maharajas of Cooch Behar. Meanwhile, Sunity’s three daughters—Girlie, Pretty, and Baby—received modern educations and were skilled in riding, tennis, and dance. Girlie married a respectable non-royal Brahmo man from Calcutta, while Pretty and Baby married Englishmen and settled in England. Ironically, their westernized upbringing made them unsuitable matches for Indian maharajas of the time. Sunity, despite her love-hate relationship with Britain, believed her daughters would thrive there.

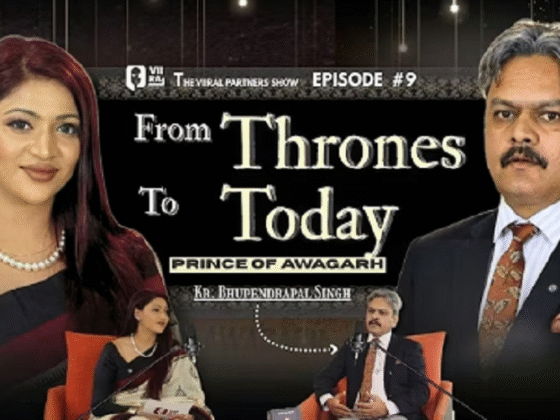

Exploring More About Indian Royalty

As a child, I was fascinated by princesses. Now, as an adult, I’ve become a serious Indian royalty enthusiast. In addition to The Autobiography of an Indian Princess, I’m enjoying Lucy Moore’s Maharani: The Extraordinary Tale of Four Indian Queens and Their Journey from Purdah to Parliament and Pramod Kumar’s Posing for Posterity: Royal Indian Portraits.

I also recommend the NDTV series Royal Reservation, which offers inside tours of various palaces and candid interviews with modern royals. One episode featured a Muslim begum in Gujarat who hopes to convert her palace’s zenana into a hotel for female tourists—a fascinating blend of tradition and modernity.